A Look Back And a Provocative Look Ahead

Welcome to an anniversary party— one played out not in a ballroom or country-club drawing room but in pages of cold print.

The milestone we are marking is our 10th anniversary of publishing Digital Transactions, an enterprise we rather immodestly think of as the first such journal to treat electronic payments without regard to medium. Whether it was a card transaction, an automated clearing house payment, or a check turned into bits and bytes, it was—and is—an electronic transaction to us, and worthy of study. Nor were we wedded to any particular constituency. We carefully embraced banks, merchants, processors, and all others who made this world spin.

That was our stance when we printed that first issue in January 2004. It remains so today, and will remain so into the future. You can see that philosophy at work in the pages that follow. These constitute a review of 10 years of coverage arranged thematically across 10 major areas of interest to electronic-payments professionals.

But this is no mere sojourn down memory lane. We have invited 10 industry experts to join the party by giving us their thoughts on how each theme is likely to unfold over the next 10 years. Will we still be writing checks in 2024? For the answers to that and nine other provocative questions, read on.

We hope you enjoy this special report. Thanks for your readership over the past 10 years, and thanks in advance for your patronage in the years to come. Whatever you do, don’t stop reading. The real party is only just beginning.

The ACH

The Original Electronic-Payments Network

A Look Back

For all the slickness and buzz surrounding emerging forms of payment, no journal covering the transactions business can afford to ignore the decades-old automated clearing house network. Not only is it a massive network in its own right, reaching into nearly every financial institution in the country, but also it undergirds many of those snazzy new payments schemes, silently fulfilling their promises of ubiquitous availability.

In September 2006’s “The Next ACH,” we covered a number of ideas to make automated clearing house payments smoother and more modern. These included check conversion and something then called credit push, a measure to persuade consumers reluctant to disclose their credit or debit card numbers online to jump into Internet payments by allowing them to tap their checking accounts.

Down the road, back-office conversion beckoned. This service enabled merchants to scan consumer checks in their back offices and then submit their transactions electronically as ACH debits.

“Ordering Priorities,” April 2011, examined new initiatives from NACHA, the payments organization that sets the rules for the automated clearing house network. In an effort to further commercialize the big, little-known network, NACHA worked on projects including retail Internet payments via Secure Vault Payments (the new name for credit push), a new electronic-billing system, and health-care payments. But obstacles abounded as banks looked to protect their interests.

The ACH clung to its two-day clearing model in the age of mobile access, same-day delivery, and faster everything. In September 2011, we reviewed the struggle to implement same-day clearing of ACH transactions in “From Tomorrow to Today.” The ACH was falling behind even Check 21, which because of image exchange was in many cases clearing checks the same day they were presented.

But same-day is only a stopgap. The next step? Real-time settlement.

Will Same-Day Payments Come to the ACH?

A Look Ahead

By Bob MearaSenior Analyst, Celent LLC

In considering faster payments, there are at least two considerations: What is meant, exactly, and who is the customer? Who stands to benefit from faster payments?

Particularly in the case of real-time payments, it is important to distinguish among notification of payment, payment guarantee/funds availability, and actual settlement. Accelerating the first and second are more important than the third, and less costly to bring about.

Many assert strong and growing consumer demand for faster retail payments. We see more interest than demand, particularly if costs are factored in. Celent surveyed more than 1,000 U.S. consumers in August 2013. In part, we explored payment expectations. More consumers expect instant confirmation of payment (59%) than expect real- time gross settlement (42%). Other factors weigh more heavily than speed. Merchants and regulators are more invested in faster payments than are consumers. Faster payments mean earlier access to funds (retailers) and less systemic risk (regulators).

Faster payments are a certainty—in time. What’s far from certain is how it comes to be and what rails are used. Some advocate using the automated clearing house network. I disagree. Moreover, I find the current dissatisfaction with the ACH amusing. Designed as an efficient, electronic, float-neutral payment system, the ACH is highly effective at fulfilling its designed purpose. More recent demands on the ACH, while not without efficacy, have also resulted in increased cost and complexity.

Same-day ACH, in my opinion, is simply not compelling. If enacted through a rules change and offered optionally at a premium price, it may succeed, but would result in precious little use. Real-time ACH would be altogether different—a fool’s errand in my opinion. The ACH works splendidly when used as designed.

Checks In Transition

Checks’ Swoon And the Rise of Check 21

A Look Back

When we laid the foundations for this magazine in 2003, we purposely included all forms of consumer-based electronic payment, whether card-based or not, and that included checks. Why? Because they were becoming less dependent on paper and more electronic in nature, a trend that took on more urgency with the Check Clearing for the 21st Century Act, better known as Check 21.

We took our first comprehensive look at this law months before its effective date. In our May/June 2004 issue, our cover story, “The Race to Build Image Exchanges,” chronicled how rival data processors were scrambling to build networks to swap electronic check images and lock in volume early. As an executive with one nascent exchange put it, “We’re in the early stages of a land grab.”

Then, we provided an update on the astonishing effects of image exchange in October 2009 with “Check 21 Five Years Later.”

The new law laid the groundwork for the transit of check images, rather than the original paper, for settlement, and it wasn’t long before banks and merchants were reaping the benefits.

For financial institutions, the advantages included less expensive check-processing costs. But image exchange also led to the imaging of checks by merchants and, ultimately, consumers themselves, in a process called remote deposit capture. We looked at consumer capture, for example, in April 2009 in “A Captivating Deposit Solution?”

The next logical step could be something called the electronic payment order. This will eliminate paper altogether by letting consumers create a check image on their mobile device, then send the image to a payee. We were among the first to describe this technology in the Trends & Tactics section in our February 2010 issue with “Guess Where Check 21 Is Going Next?”

Will We Still Be Writing Checks in 2024?

A Look Ahead

By David WalkerPresident and Chief Executive Officer, Electronic Check Clearing House Organization

The answer is yes. Perhaps a more important question is: Why? Answer: Because check payments contribute value across a very broad spectrum of users. The existence of that value is self-evident. Billions of checks for trillions of dollars continue to be issued despite decades of extensive efforts to eliminate them.

Check payments are used in almost every payment scenario between all parties. No other payment type has the ubiquity of users directly issuing payments without the involvement of other entities. Until these users replace all their checks with other payment types for all payment scenarios, the lowly check will endure.

With more than 20 billion checks written annually, consider one check scenario that has proven most difficult to eliminate: business-to-business checks. Businesses opine that check payments are not problems needing solutions. Replacing checks with another payment type would require businesses to make new investments. When given the choice between new administrative overhead costs (e.g. for payments) or investing in the goods and services that create business profits, the preferred choice will always be profits. Businesses have little incentive to replace checks.

As long as checks are being issued, such as business checks, the system must be efficient and well maintained—a more efficient check is an even better check. The investments made to replace paper with images have created greater efficiency and significant value. These qualities, efficiency and value, can be enhanced even further as checks become fully electronic.

Checks in 2024? Yes, but fully digital—including their creation.

Debit

Durbin Transforms U.S. Debit

A Look Back

People love it or hate it, but for journalists, the Durbin Amendment is the gift that keeps on giving. U.S. Sen. Richard Durbin’s amendment in 2010’s Dodd-Frank Act radically upset the debit card status quo by regulating interchange and overturning longstanding transaction-routing practices, guaranteeing that reporters covering the payments industry would have controversies to cover for years to come.

Durbin-related issues have made no fewer than four Digital Transactions covers. The first, “How Durbin Erases Routing Rules,” (January 2011), previewed the law’s seemingly esoteric but revolutionary provision that would transfer control over transaction pathways from issuers and networks to merchants—15 months before the Federal Reserve Board’s regulations implementing that part of the amendment took effect.

Durbin’s routing provisions and ban on exclusive network-issuer debit partnerships shifted more than 50% of volume from Visa Inc.’s dominant Interlink PIN-debit network to competitors (“The Great Debit Network Reshuffle,” October 2012). MasterCard Inc.’s Maestro network, until then a minor player in U.S. debit, appeared to be the big winner in the early going.

The “Reshuffle” story came just a month after we detailed a key component of Visa’s Durbin recovery strategy in “What’s This FANF Thing All About?” (September 2012). The story assessed Visa’s mysterious Fixed Acquirer Network Fee, which rewarded merchants and acquirers for sending more transactions Visa’s way. Durbin also affected how big banks could play in the prepaid card markets, (“Don’t Fence Me In,” March 2012.)

Last July, U.S. District Judge Richard Leon overturned the Fed’s rule implementing Durbin, saying the board did not follow Congress’s intent by setting the interchange cap too high. Leon also suggested that merchants might be entitled to even more routing choices. The Fed is appealing.

Anybody want to bet that the Durbin Amendment won’t be on our cover again?

Will We Ever Get Finality on Durbin?

A Look Ahead

By Tony HayesPartner, Oliver Wyman

In mid-2003, MasterCard and Visa settled the 7-year-old “honor-all-cards” lawsuit on the eve of trial. At the time member-owned associations, Visa and MasterCard agreed to pay approximately $3 billion, temporarily lower signature-debit interchange, and change their tying rules.

If history is any guide, it could be another seven years before implementation of the Durbin Amendment is resolved. If the clock starts from the Federal Reserve’s issuance of its Final Rule for Regulation II (the amendment’s official name) in June 2011, that would suggest we might have clarity by mid-2018.

But even that is probably too optimistic. First, of course, is U.S. District Judge Richard Leon’s July ruling that the Fed “clearly disregarded Congress’s statutory intent.” Is the interchange cap of 21 cents plus 0.05% for non-exempt debit card issuers too high? Should merchants have routing choice for every debit transaction (not card)? We’ll see how the appellate court rules.

Second, irrespective of the court decision, the debate will continue. The numbers are simply too large for either merchants or issuers to stop pressing their case. In 2004, there were 18 billion debit transactions; by 2013 they have tripled to an estimated 55 billion. For better or worse, the Fed is tasked with reviewing and, when appropriate, resetting the debit price cap every two years, so we should expect periodic adjustments—and acrimony.

Third, and perhaps most important, the debit market is changing. The U.S. may be migrating to Europay-MasterCard-Visa (EMV) chip cards, which introduce a whole new set of transaction-routing dynamics. Or the U.S. may bypass EMV entirely and move straight to mobile payments.

While Durbin is defined by a debit account, not a debit card, new payment technologies and routing options will almost certainly mean more changes to come.

EMV

The Struggle for U.S. Chip Cards

A Look Back

For something that supposedly is inevitable, the Europay-MasterCard-Visa chip card seems extraordinarily elusive in the United States. Apart from a comparative handful of international travelers who are encountering increasing hassles overseas using their magnetic-stripe payment cards from U.S. banks and credit unions, hardly any Americans have EMV cards yet.

Even though all other major industrial countries have adopted EMV, it’s just not that easy switching from the fraud-prone but still fast, cheap, and generally reliable mag stripe, as noted in our October 2010 cover story, “The United States of Chip-and-PIN.” That story was published about 10 months before Visa Inc. got the U.S. EMV ball rolling by issuing its roadmap—not an actual mandate—with various carrots and sticks to spur merchants, card issuers, and processors to begin the conversion to chip card (and mobile) payments.

Americans could learn some lessons from neighboring Canada, which recently adopted EMV (“Canada Puts Down Chip Card Roots,” June 2011).

But merchants, who are expected to bear most of the conversion costs, still had plenty of reservations after Visa’s announcement, though some welcomed the changeover (“Merchants Zero in on Payments,” October 2011).

One huge hurdle that Canadians, Europeans, and Asians don’t have to worry about clearing is the Dodd-Frank Act’s Durbin Amendment, which requires that U.S. merchants have alternative transaction-routing choices. Easy to do with mag stripes, very difficult with EMV chips (“Durbinizing EMV,” March 2013). The major general-purpose networks and electronic funds transfer networks are trying to find a so-called common identifier, a project that could get even harder if a court decision that would require merchants to have even more routing choices prevails on appeal.

Will EMV Investments Be Worth It?

A Look Ahead

By Julie ConroyResearch Director, Aite Group LLC

In 2024, with the U.S. migration to Europay-MasterCard-Visa chip cards behind us, will the payments industry deem it worth the blood, sweat and billions? And will the U.S. even move to EMV given the uncertainty created by U.S. District Judge Richard Leon’s snarky opinion last summer?

The answer to the latter question is “yes.” There are too many factors pushing the U.S. toward EMV, though the disquiet caused by Leon’s decision overturning the Federal Reserve’s Durbin Amendment rule will likely result in a delay. Ten years out, the view of EMV is unlikely to be much different than it is today.

Issuers are embracing the concept. As the last G-20 country to adopt EMV, U.S. issuers are feeling the pinch, with counterfeit fraud losses rising 30% to 50% on a year-over-year basis. The promise of credit card universality also is fading, as it is increasingly difficult for Americans to use the antiquated magnetic stripe abroad.

Merchants, however, are less than thrilled. EMV to them means expensive hardware and software upgrades, along with an inevitable spike in card-not-present fraud. The confusion surrounding Durbin’s dual-routing procedures only adds to the consternation. This view is unlikely to change, although if networks and issuers find a way to reduce the CNP fraud pain, merchants will be slightly less disgruntled.

The net is that the EMV migration, though deemed necessary and overdue by some, is viewed by many merchants as another move in the long U.S. payments chess match. What makes one side happy is unlikely to be viewed favorably by the other, now or 10 years from now.

Interchange

Is the Price Ever Right?

A Look Back

What merchants pay for electronic-transaction acceptance and processing is a subject we have covered from the very beginning, since it goes to the very heart of commerce via digital transactions.

In our very first issue (January/February 2004), our cover story, “Behemoths Besieged,” detailed how Visa and MasterCard found themselves locked in combat with merchants, regulators, and each other over a range of issues, including interchange fees. In a prelude to the battles to come over the Durbin Amendment, merchants had just scored a major win in court, forcing what were then the card associations to cut debit card interchange and alter their honor-all-cards policies.

The interchange wars simmered for years, with merchants mounting a double-pronged attack on the acceptance costs of both credit and debit cards. They learned from past mistakes, and focused their efforts on Capitol Hill. The payoff was the Durbin Amendment, part of the massive Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, which for the first time made caps on debit card rates the law of the land. Fresh from that signal victory, merchants began contemplating similar restrictions on credit card interchange, the bread and butter of the electronic-payments business.

In February 2012’s “Will Credit Cards Be Next?” we documented how antitrust litigation started in 2005 could reshape credit card interchange and set the stage for federal intervention. That litigation ended up in a settlement that summer that remains contentious to this day, with many big-box merchants opting out to preserve their rights to bring suit on their own or collectively. Nonetheless, a federal judge last month granted final approval of the agreement.

Nor have we ignored the basics of do-it-yourself interchange control. In the midst of a withering recession, April 2009’s “Becoming a Master of the Interchange Universe” detailed how merchants who are willing to tackle the bewildering welter of interchange rates can reduce the levy that accounts for most of their acceptance costs.

Are Credit Interchange Caps Inevitable?

A Look Ahead

By Steve MottPrincipal, BetterBuyDesign

The answer is yes. The continuing rancor over credit card interchange fees is reminiscent of how American society dealt with the scourge of cigarette smoking. The companies exerting market power steadfastly resisted growing opposition from the public and fought to undermine court efforts to fix what the market (or legislatures) couldn’t.

After decades of untold costs to financial and human well-being, the entrenched companies finally succumbed to enlightened legislation that protected society.

The Durbin Amendment was like the first big court victory against the tobacco companies. There will be many more—until the day comes that banks and card networks are forced to price on real value added (not the outdated notion that credit cards help either merchants or consumers), and actually have to compete.

We’re already seeing the beginning of the end of card-not-present designations, rate premiums, and one-sided liabilities. Lower rates agreed to by issuers in special deals with merchants are expanding steadily. Next to go will be ad valorem rate components applied to purchases beyond a predicted risk level.

And then issuers will bifurcate the costs of credit risk (which can be valuable, so long as banks quit competing on marginal credit risks and incurring charge offs that eat up half their income), and rejigger the real costs of settling the payment (which will drop to a natural range of 5-to-10 cents per transaction once payments move to real time, and merchants quit financing issuer rewards).

On average, credit card interchange will drop in half in five years, or merchants will go back to financing their own credit.

ISOs

The Evolution of ISOs

A Look Back

Ten years ago, consolidation was reshaping the independent sales organization segment of the payments industry. As reported in “Behind the ISO Consolidation Trend” in the January/February 2004 issue, ISO valuations were increasing, with TransFirst Holdings Inc. seeing multiples increase 20% in the prior year to as much as four times net revenue.

New money, in the form of intensified private-equity investments, fueled many of the consolidations. But emerging technology and a thirst for added value also were factors as buyers sought a way to sprint ahead of competitors. The resulting environment meant smaller ISOs had to craft strategies to contend with a growing number of larger competitors.

New payment technologies could present new opportunities for independent sales organizations as merchants became saturated with payment terminals, as we reported in “A New Dance for ISOs” in April 2006. PIN debit was a natural complement to traditional credit and debit card processing, but other services like recurring bill payments and prepaid cards could present challenges for ISOs, especially smaller ones reluctant to adopt them, observers said.

But by 2012, the imperative to experiment with new technologies was becoming too compelling to ignore, even for small fry. For example, “Innovative ISOs,” April 2012, reported on the increasing trend toward integrated payments and business-management software.

Meanwhile, state and federal regulators began casting a wary gaze on merchant-processing companies, with a flurry of Federal Trade Commission activity in 2013. As we reported in September 2013’s “ISOs Enter the Age of Regulation,” one reason was that the FTC could go after bigger targets, like telemarketing fraudsters, by shutting down their payment-processing accounts. “The acquiring business, including the ISO business, has always sort of flown under the radar of the regulators,” said attorney Holli Targan, partner with Southfield, Mich.-based Jaffe, Raitt Heuer & Weiss PC. “That era is over.”

Who Says ISOs Should Sell Transactions?

A Look Ahead

By Adil MoussaPrincipal, Adil Consulting

In 10 years, independent sales organizations will be in the middle of a remarkable shift, migrating from making the bulk of their revenue from card transactions to fees collected from selling applied software solutions. The reason behind this shift is that merchants are more willing to spend money to acquire customers or to resolve practical problems than to pay what some consider a “credit card acceptance tax” on each transaction.

Solutions like daily deals proved that merchants are willing to pocket as little as 25% of a transaction’s face value if they could acquire new customers. Yet, merchants haggle with ISOs over a couple of basis points when negotiating processing fees.

The road of least resistance is to charge a high percentage on the transaction or a recurring flat fee on the software solution instead of using the banking model, which is ineffective and poorly suited for ISOs. In the banking model, banks have multiple sources of revenue from merchants, including loans, lock box, checking and saving accounts, credit cards, debit cards, etc. Transaction processing is a very small part of the bank’s revenue. However, 95% of an ISO’s revenue comes from merchant processing.

So why keep a maladjusted source of revenue and force the market into margin compression?

ISO means independent sales organization. It has never been specific only to merchant acquiring. As long as ISOs are selling something, why not sell solutions that merchants desire and make larger revenues in the process?

The reality is that software vendors need a selling arm to reach their prospects. Another reality is that ISOs will never go away because merchants will always prefer to buy from people they trust and that take good care of them. The only thing that changes is the product sold.

Mobile Payments

NFC vs. All Comers

A Look Back

The card networks began experimenting in the early 2000s with technology that would let consumers replace cards with mobile phones. One of the most promising of these technologies turned out to be an interactive contactless protocol called near-field communication, or NFC for short.

Our first comprehensive look at NFC, March 2006’s “Near-Field Dreams,” laid out both the technology’s huge promise and vexing problems. On the one hand, NFC could let consumers use their handsets to make payments, download content from so-called smart posters, and receive and redeem offers. On the other, NFC paved the way for mobile carriers to muscle in on transaction revenues, to the dismay of banks and card networks.

Years of wrangling among these parties ensued, as documented in “Delayed Launch,” June 2010. NFC seemed stuck in perpetual pilot mode as banks, card networks, and mobile operators haggled over pricing, revenue, and control issues. As one observer put it, the trouble with NFC was that there were simply too many mouths to feed. Meanwhile, consumer interest flagged, and workaround techniques emerged, such as RFID stickers.

What could bail out NFC—and the whole concept of mobile payments—was the smart phone. With these gadgets in consumers’ hands, marketers could send real-time offers and let users redeem loyalty points at the moment they were paying for merchandise—a vision we outlined in “The Age of Offers,” September 2011.

But the proliferation of mobile payments has a downside, too, as we explained in June 2012’s “Cybercrime Eyes Mobile.” With mobile payments, payments processors don’t control handsets. Consumers do. How to harness the smarts in smart phones to overcome that problem?

Will NFC Be Superseded?

A Look Ahead

By Rick OglesbySenior Analyst, Aite Group LLC

What the payments world erroneously calls NFC, or near-field communication, might more accurately be called card emulation. In this approach, payment card information is stored in a secure memory chip in the mobile device and at the appropriate time transmitted via an NFC radio to an equipped payment terminal. In this way, card payments can migrate from a plastic card form factor to a mobile one.

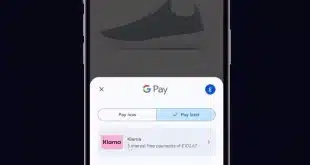

However, these solutions have not yet seen significant adoption. Card-emulation pioneers Google and Isis have been unable to scale their relationships with financial institutions, merchants, and consumers. Apple is spurning the technology, and even the payment networks are shying away from card emulation in their own digital wallets.

So we must ask ourselves if this solution is addressing the right question. Within the mobile form factor is a card transaction even relevant?

When a consumer uses a mobile device to shop, payment information can be exchanged at any time and from anywhere, not just at the point of sale. Additionally, payment data itself can be irrelevant (in the case of PayPal, Square Wallet, and some others, the merchant and consumer exchange identity information, not payment information).

Payment networks oversee the exchange of payment information and provide the mechanisms through which acquirers and issuers are able to monetize those exchanges. If payment-data exchanges migrate away from the point of sale, then acquirers will see massive disruption. If payment information exchanges give way to identity-information exchanges, then payment networks and issuers will face similar disruption. If card emulation continues to flounder while the mobile device flourishes, then the message is clear: Get ready for major payment-industry disruption.

NFC and card emulation are not the same thing. Card emulation is just one of the ways that NFC technology can be used to complete a payment, and no other device-to-device technology is on a faster deployment cycle. Therefore, the future of NFC looks bright. The future of card emulation, however, is another story.

Prepaid

Pay-Ahead Plastic Grows up

A Look Back

Consumers who seldom or never used a bank totaled an estimated 48 million in 2005, all potential consumers of prepaid cards, according to “The Promise of Stored Value” in the July/August 2005 issue. The article examined potential ways to make money from offering prepaid cards. The payoff was in capturing an estimated $100 billion the non-banked spent in cash for rent, utilities, and everyday purchases.

“Ultimately, these players hope to create a full-blown menu of financial services not only for the non-banked but for the under-banked, that is, consumers who have a limited banking relationship, such as a savings account but no DDA or credit card,” the article surmised.

More companies increasingly opted for using prepaid cards to deliver rebate funds to consumers, as we noted in “Prepaid Plastic: The Latest Consumer Spiff” in the April 2009 issue. Using cards could help marketers reclaim unused rebate funds easier than with rebate checks. Unused rebate checks fall under unclaimed-property laws in many states, while prepaid rebate cards do not. But they may not make sense for incentives of less than $10.

By 2011, lawmakers and regulators had begun to scrutinize the payment product, we explained in March that year in “Prepaid Cards’ Big Bullseye.” Efforts included requirements to fully disclose fees and restrict the types of fees that could be charged. But prepaid providers were concerned that more regulation could mean higher costs and lower fee revenues in a business with slim profit margins.

Regulatory measures under discussion included implications of the Durbin Amendment to the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act and potential regulations from the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network.

Will Prepaid Lose Its Popularity?

A Look Ahead

By Ben JacksonSenior Analyst, Mercator Advisory Group

To answer the question, “No.” Among all the major payment types, prepaid cards will grow in popularity because of their value to program managers, issuers, and cardholders as a tool that can steer behavior and reduce risk.

Steering behavior is a goal of many prepaid providers and users. Incentive programs use prepaid cards as a way to deliver rewards. Closed-loop cards can restrict spending to a single merchant, and restricted authorization networks can limit spending to a specific set of merchants, such as pharmacies for health-savings accounts. Individuals use prepaid cards to direct the spending of friends and family.

Reducing risk is a goal for prepaid users ranging from large corporations to individuals. Prepaid cards reduce risk because they allow for payments that do not require the extension of credit or the exposure of a bank account.

Prepaid cards reduce risk in other ways. For example, large banks use general-purpose prepaid cards as a replacement for checking accounts when potential customers have bad credit scores or histories with Chexsystems, a bank-account scoring service. Small businesses use prepaid cards in place of petty cash to track how funds are spent. Individuals use prepaid cards to shop online without exposing credit or debit cards to hackers.

Because of these features, prepaid is often the first choice for payments in connection with launching new technologies. For example, the growth of mobile payments began with closed-loop prepaid, making Starbucks Coffee Co. the leader in mobile payments.

With their versatility and security, prepaid cards will continue to make up a significant part of the payments landscape, even if “cards” themselves fade away.

Regulation

Regulators Eye Electronic Payments

A Look Back

As an integral part of banking, a heavily regulated industry, the merchant-acquiring department happily escaped close government scrutiny for decades. But all that began to change about four years ago.

There was the Durbin Amendment, of course. But in less dramatic fashion, the Federal Trade Commission and bank regulators began to increase their monitoring of non-bank companies that work with acquirers. “The Baby And the Bath Water” (December 2013) noted how the FTC has proposed an outright ban on telemarketers’ use of four electronic-payment methods: remotely created checks, remotely created payment orders, prepaid authorization codes, and remittances.

The clear message to acquirers: Regulators are serious about policing ISOs and other processors that handle payments for suspect companies that generate fraud complaints from consumers.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. also is keeping a closer eye on third parties it believes could bring risk into the banking system. And the young Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is nipping at the edges, though it hasn’t yet promulgated regulations that affect acquirers in a big way. But government is very closely monitoring the development of virtual currencies, as detailed in “So You Want To Get Into Digital Currency” (July 2013).

If the feds aren’t keeping payment-industry lawyers busy enough, states are producing plenty of billable hours for them. Forty-seven states require non-bank money transmitters to be licensed, a system critics say imposes needless burdens on providers and thwarts startups that could bring lower costs and valuable new services to market (“States’ Rights,” October 2013). Supporters say licensing protects consumers, while still others suggest that a single, federal licensing system would simultaneously provide protections and promote more competition.

How Much Regulation? It’s up to You

A Look Ahead

By Eric GroverPrincipal, Intrepid Ventures

With light regulation, unprecedented retail-payments competition and dynamism, greater nonbank participation, mobile-phone ubiquity, and a wave of new innovators, the next decade should be a payments-industry renaissance.

There is, however, a grim alternative path: the Federal Reserve’s regulating debit interchange and routing, and taking a greater role in governing the automated clearing house; also, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau mandarins flexing their unchecked might and fishing for new areas to regulate.

Washington has never been more likely by law or regulatory diktat to intervene under the banner of promoting payments security, efficiency, and fairness. Paraphrasing Leon Trotsky, the payments industry may not be interested in Washington, but Washington overlords are interested in it.

Whether in a decade payments is a public utility or the regulatory landscape is benign depends on politics, which the industry can influence. Consider a nuclear winter: President Elizabeth Warren, Senate Majority Leader Dick Durbin, Senate Banking Chairman Jack Reed, House Financial Services Committee Chairwoman Maxine Waters, Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, and the CFPB unbridled.

Alternatively, imagine a Speaker Jeb Hensarling eliminating the CFPB or constraining it with a bipartisan board, Congressional budget approval, and a narrower mandate; Congressmen Chaffetz and Owens’ Durbin-repeal bill being revived; and the Fed divesting its ACH processor.

Politics and policy matter.

A somnolent payments industry was wrong-footed by Senator Durbin. To prevent worse, the industry must make an affirmative case in the political arena to inform consumers (voters) that a light regulatory regime, where Washington plays the role of night watchman rather than central planner, best promotes innovation, competition, and consumer value.

Security/PCI

Security’s Perennial Challenges

A Look Back

Protection against theft and fraud is an issue with any payment system, be it barter, cash, checks, credit and debit cards, or other forms of electronic payment. PCs and most recently mobile devices are now pieces of the security puzzle. Thus, security has been part and parcel of our coverage since the magazine launched.

Our second issue’s cover story, “The Malware Menace” (March/April 2004), reported on how transaction networks had “sustained a barrage of viruses, worms, and other variants of malicious code.” The piece predicted that “it’s only going to get worse as hackers grow more sophisticated and the attacks more frequent.” Ten years later, does anyone care to object?

Despite constant improvements, electronic payments retain numerous vulnerabilities. “The New Risk in PIN Debit” (June 2006) noted that PIN-protected debit cards have their own weak spots, though their fraud rates are much lower than those for signature-debit cards. “When Passwords Fail” (January 2008) discussed related issues.

And with mobile payments coming on strong, a host of new security issues arise, especially since hundreds of thousands of new card-accepting merchants use their personal smart phones or tablet computers to process transactions. We described a multinetwork effort to create a new tokenization regime for digital payments in “Token Specs: Curb Your Enthusiasm,” November 2013.

Of course, no fraud discussion is complete without mentioning the Payment Card Industry data-security standard, or PCI—the common set of security rules for processors and merchants that accept general-purpose credit and debit cards. PCI, much derided by many merchants and others in the payments industry but viewed as indispensable by others, has been the subject of numerous Digital Transactions stories.

Most recently, we reviewed the standard’s latest upgrade, Version 3.0, with “Changing the Checkbox Mindset” (December 2013). Our “PCI Compliance—Once Is Not Enough” special report (March 2008) discussed how meeting the standard’s 200-plus sub-requirements by no means meant that a merchant could ease up on fraud control.

Will PCI Be Obsolete in 10 Years?

A Look Ahead

By Avivah LitanVice President and Distinguished Analyst, Information Security, Gartner Inc.

I certainly hope so and I know that most of you out there who are burdened with PCI compliance hope so as well. Version 3.0 of the Payment Card Industry data-security standard, effective this month, holds nothing radical or revolutionary. Just more of the same with minor improvements around the edges.

PCI is a very effective catalyst for securing security budgets in organizations not prone to spend money on such matters, and many security managers are therefore secretly grateful for the need to comply. But it doesn’t make sense to patch an inherently insecure payment card system, and it makes even less sense to ask merchants in the business of selling goods and services to become security experts or face stiff fines and the threat of going out of business.

This systemic dynamic is not a problem with PCI—it’s a problem of the current payment card ecosystem and its dominance by card-issuing banks for Visa and MasterCard.

Thankfully, there are innovative payment schemes that are much more secure and sometimes even anonymous coming to the fore, with the best example being Bitcoin digital cash. Over time, merchants will turn to these alternatives, where they pay lower fees for accepting them and avoid the heavy costs that come with PCI, mainly because the systems are more secure to begin with and don’t rely on extremely vulnerable magnetic-stripe technology.

In 10 years, to stay competitive, banks and card brands will have no choice but to offer advanced payment systems, where security is baked in. This will finally render PCI obsolete and useless.